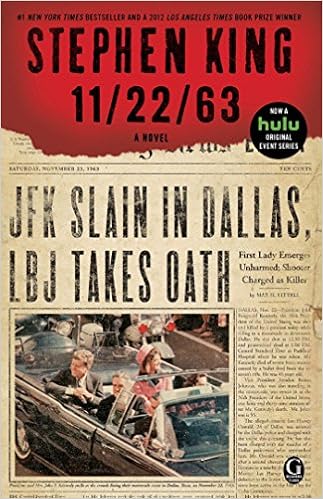

Our cultural memory is built around a series of events that resound in our collective memory. Some of these are good like the date man first walked on the moon, but many are terrible to recall. Yet we recall them when each anniversary comes around and remember where we were when "it" happened. For my Dad, his first "It" date was December 7, 1941. His childhood memories were divided by the day he went fishing and came home to a country at war. For me and a lot of other Baby Boomers, our first "It" day is today. November 22, 1963. President Kennedy's assassination threw such a big rock in our river of memory that the ripples hit our personal lives.

Those ripples are one of the big themes in the King novel titled with that date. In a way, it's a normal time-travel tale: a man goes back in time to prevent something bad and finds out success can breed a bigger failure. In another way, it's much more than that; it's a tour of history and a trip through a human heart.

King's research in story tale showed me I don't know very much about the event I'll probably remember for the rest of my life. Yes, I remember my mother crying uncontrollably when the president was shot and how so many grown-ups around me hated, just hated he'd been killed in our state, Texas. But I didn't know the assassination probably wasn't Oswald's first attempt; seven months earlier, a retired army general had been shot at in his home and evidence indicates Oswald pulled the trigger. That information suggests something in Oswald's motive to me: he was killed people for fame, not politics. The segregationist/arch-conservative views of the general were the opposite of Kennedy's liberal ideals. Oswald wouldn't have targeted both men because of their deeds; they were political opposites. What the victims had in common was their celebrity status which makes Oswald like Mark David Chapman: someone so determined to be remembered, they'll kill to get into history.

11/22/63 also looks at how America has changed in fifty plus years and how we've stayed the same. Our wage rates and prices may change but our attitudes towards these don't. There are still good people and bad ones and a lot of souls caught in between. We all know we live in a global economy but we tend to look at the world through home-town glasses. We still root for the hero and cry when he loses. We still get up again after we fall. And, like every generation before or since, there are dates we will never forget.